Charm & Pedigree

It was during Christopher Columbus’s arrival in Cuba, back in 1492, when Europeans learned about the existence of tobacco. Their harbingers found local islanders enthusiastically plunged in the ritual of blowing smoke out of a short musket of twisted leaves, wrapped around in a very rudimentary fashion, that dwellers called cohiba or cohoba. Though it was originally labeled as a devilish act, the habit of the Cuban aboriginals wound up capturing followers, either as snuff or rolled up in leaves. Cuba’s black tobacco jumped over the Caribbean boundaries to conquer the entire planet through space and time And it didn’t take a lifetime to do so in the Old World.

Only a few decades were good enough for the smoke of Cuban cigars to spread around the world, even regardless of tight restrictions the Inquisition meant to impose by labeling anyone who would consume it as a demon.

The prodigious nature of the Cuban archipelago favored the development of this crop, “a special gift given to Cuba,” as Narciso Foxa chanted. Consequently, this gave birth to an industry, a way of living marked by close relation-ships between man and tobacco from the plantation to the point when it goes up in smoke, smells and ashes.

The growers pamper it and look at it as something that needs all the care in the world, a reason why they stick to the plants for several months until the leaves finally reach the size and quality they desire. Those who roll the leaves by hand use the best of their talents and senses to make the whole toilsome process flawless for such a delicious and lovely natural product, and those who puff on cigars cherish them before lighting them in a brief farewell of love, ready to see them burn away into winding hazes of bitter aroma.

The peerless conditions of the island nation’s environment became the foundations for such a delicate artwork. But that would have been to no avail without the experience and expertise of Cuban rollers that for centuries have kept tabs on the behavior of this plant to make the most of it in the field, the indus- try and the trade.

This longstanding and rewarding learning process has put the name of Cuba on the entire world map by the hand of habanos, for always and to date seen as “an encouragement and a token of all men who can afford individual pleasures and boast it in the face of pleasure-restraining conventionalisms,” as Fernando Ortiz wrote.

A mollycoddled plant

Having a good vega –the name of both the tobacco plantation and the farm– is a tough job to do. Tobacco growers are sensitive, hardworking and nitpicking people that spend most of their time in the farm because tobacco tasks have no end. The soils, even though they might or might not be used as croplands, must be rotated every so often to keep the grains loose and make the brittle tobacco seedlings thrive, get hefty and take in all necessary nutrients from the soils under the best conditions possible. These tasks should only be done with the help of oxen. By summertime, growers are supposed to plow the land from time to time and by the month of November, they must start working on the seedbeds. That leads to the most painstaking part: catering to the plantation –up to 150,000 plants in the case of shade-grown tobacco– that will be ready for harvesting some 50 days later.

Through all this time, each and every plant must have its buds removed many times over to let the leaves grow plentifully before they can be plucked out in several rounds from the ground up, beginning with the bottom leaves and winding up a few days later with the top leaves. This procedure is applied to both shade-grown and sun-grown tobacco. Either way, tobacco harvesting is extraordinarily complex and painstaking, and it requires countless visits to the plantation and plant-by-plant caring.

The Curing

As meticulous and demanding the harvesting is, so is the curing process. Once they have been picked, the leaves are sewed to long wooden rods and whisked off to the curing barns where they are subjected to a natural drying process. They turn from dark green to yellow and finally to golden-reddish some 45 days after –depending on weather conditions.

Each rod yields a couple of sheaves that are piled up in bundles of eight before the leaf nerves are removed for the making of the filler. The nerve-removing process also takes a number of steps, from untying the sheaves from the rods to the moment the leaves are packed up and whisked off as raw materials to the cigar factories.

This means that the job in the field is followed by a multitude of other complicated and meticulous tasks always characterized by nonstop selection, classification and improvement of leaves, as if it were a long chain of tiny details in which experience, skills, rigor and individual ingenuity count decisively in providing the industry with top-notch raw materials.

The hand-rolling process

The factory’s workshop is the one place where rollers turn the tobacco leaves into consumable items. Even though this is indeed a highly complicated and painstaking job, cigar rollers are capable of working wonders out of raw materials that look quite ordinary to most of the people. Other anonymous artists are supposed to do their share faultlessly before and after this process in a bid to let rollers get their job done and produce top-quality, flawless end products in terms of looks, smell and taste.

The point is the tobacco rolled to be smoked as habanos has never been gauged in terms of quantitative outputs, but rather for the excel lence they show off –a golden rule for the Cuban cigar-making industry that’s always determined to look into its own history, cultural values and traditions, and that’s nothing but a blend of God-blessed nature and human transcendence that have given birth to those two children of this island that have already secured a huge spot of their own in the quasi-sacred realm of pleasure.

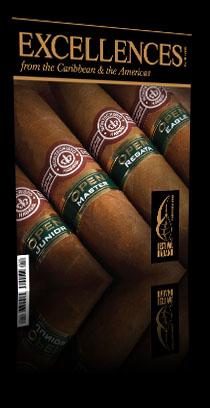

This tradition, this ability for self-regulation and self-control, this sense of respect as an expression of cult to its history are the ground-work of a prestige that has accrued in time and an undisputed leadership in the world market that this unique product has to offer. At the end, gaudy rings are wrapped around each habano and their cases show off lovely brands and labels, colorful and bucolic figures, sometimes portrayed as idols, portents and legends. The legitimate habano boasts its pedigree with such refined elegance and amusing singularities that they just don’t dodge evocations to larger-than-life historic characters, pompous garments or the sublime charm of the arts.

The bands that identify each and every brand and are wrapped around the cigars as membership codes of a big family, cannot be solely construed as elements that tell them apart or beautify them, but rather as an eternal willingness to recognize these products that, in the case of habanos, is unmistakably expressed in a flair for details.