Segura Ezquerro: Cuban or Spanish?

It’s been over two decades, in 1988, since the grand opening of an exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts, an exhibit that hasn’t grabbed all the attention it deserved if we bear in mind its tremendous significance: Avant-garde. The Emergence of Modern Art in Cuba.

Curated by two experts from the museum –Ramon Vazquez Diaz and Jose Antonio Navarrete– the exposition managed to round out for the first time ever many aspects of the development of Cuba’s modern art that were probably too close at hand and yet they had gone unnoticed. The chronology put together for the catalog is still reference material for researchers and students. In my case, as an spectator who wasn’t that much of a connoisseur on that issue at the time, what actually struck my attention was the addition of a Spanish artist who was virtually unknown among critics and experts in the field. There wasn’t so much knowledge about his relationship with the emergence and advance of modern art on the island nation. That artist was Jose Segura Ezquerro.

Segura Ezquerro, born in Almeria, Andalusia, in 1897, studied fine arts in his hometown. He graduated from the Real Academia de San Fernando, in Madrid, and among his teachers there were such boldface names as celebrated Cordovan painter Julio Romero de Torres. A few years later he moved in France, studying and working in Bordeaux, Reims and Paris until 1921. In that same year, he traveled to Cuba with his father, Eduardo Segura, an outstanding speech therapist who was curiously one of the introducers of that medical specialty in Cuba.

The painter stayed in Havana from 1921 to 1931, a period that can be labeled as his “early Cuban stage”, that coincided fully with the so-called “critical decade” that was marked by significant historic, political and artistic developments that shook the grounds of the Cuban society, such as The Protest of the Thirteen (1923), the Gerardo Machado dictatorship (1925-1933) and the New Art Exposition (1927).

There’s scarce information on his first five years in the city. Some data are known, like his friendship with Carlos Enriquez and Victor Manuel –Segura painted a portrait of the latter. There’s also evidence of his first individual exhibition held at Las Galerias back in 1923.1 At the same time, we have recently watched a series of drawings portraying children’s heads –in Spanish collections– of extraordinary quality and dated between 1923 and 1925 that paint a pretty clear picture of his going through all those years.

There’s better documentation on his experiences in working with kids at the National Institute of Hearing Impaired and Abnormal Children run by his father. In July 1927, he planned an exhibit with drawings of those infants at the Painter & Sculptor Association.

To size up how little recognition Segura Ezquerro’s artistic activities actually have, we can mention the fact that his name is mentioned in three different expositions held in 1927: Sicre in January; Victor Manuel in February, and Gattorno in March. In a way, that trio of events was in a way the threshold to the emblematic New Art Exposition opened in May of that same year. However, the exhibit the Spanish painter held in June in the same locale of Prado 44 is hardly ever mentioned. And we just want to recognize that particular event as an extension of the other three from both a chronological and an esthetic standpoint. As a matter of fact, no mention to the artist’s presence in the New Art Exposition is made either, even though he came up there with three drawings and an oil entitled “The Little Brown Girl and the Orange”. It’s worthwhile to pause for a minute in this issue of our “avant-garde onslaught” to recognize that this exposition that has always been labeled as an exhibit of Cuban art was way ahead at that time to today’s globalization issue because in addition to this Spanish artist, there were other creators, like America’s Alice Neel –Carlos Enriquez’s wife– Latvia’s Adja Yunkers, who was living in Havana at that time; Venezuela’s Luis Lopez Mendez, who worked in the Cuban capital for a few years, and Mexico’s Rebeca Peinck de Rosado.

The case of Segura Ezquerro is twice as much eye-popping because he wasn’t ignored at all by the Cuban press at the time. On the contrary, he basked in the media limelight and his work was hyped in major art magazines, like Social y Carteles, and even in some texts he was referred to as “a Cuban painter.” Jorge Mañach wrote: “our painter has managed –because Segura is ours regardless of his Spanish origin– to cash in on and cotton to the modern lesson.” A few years later, Juan J. Remos said: “when the history of Cuban painting is written one of these days, the name of Segura Ezquerro must be mentioned.” Unfortunately, many along the way have forgotten or have just put this artist on the back burner. What’s worst, the history of Cuban painting hasn’t been written yet.

Before leaving for Spain in 1931, egged on by the inauguration of the Republic, he opened just another exhibition at the Painter & Sculptor Association in 1929, that equally grabbed plenty of media hype. We can therefore imagine that before his departure Segura was a celebrated artist in Havana. Despite his stay in Madrid, we have chanced upon newspaper clippings and exposition catalogs that bear out that in no time between 1931 and 1939 he broke away from his adoptive homeland.

At the end of the Spanish Civil War, he returned to Cuba, this time around definitely. He never ever went back to his homeland. His eight-year stay in the Spanish capital –he unveiled a couple of exhibits there between 1931 and 1934 at the request of the Circle of Fine Arts in Madrid– didn’t seem to have contributed so much to the evolution of his art. On the contrary, there’s clear evidence that he kind of bogged down –at least that’s how I see it. If we compare Segura’s work in that period of time with the one of “Cubans in Paris”, we’ll surely notice the differences. While the Spaniard’s work shows a reaffirmation of his academic characteristics –though as a landscapist he sort of put a modern-oriented primitive spin on his paintings– the “Cubans” went deeper into the teachings that Paris had revealed for all of them and that they had quickly assimilated. In no way this means that Segura didn’t come up with top-quality artworks during his “Spanish period”; his Self-Portrait, the Andalusian Woman in White and some Havana scenes are good cases in point.

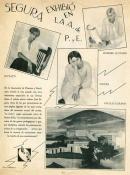

Especially his Self-Portrait, painted little after his arrival in Spain, underscores his fondness to make them in different stages of his lifetime, from his youth to his old age in the neighborhood of Marianao. The one printed in this issue was possibly painted in 1931 and the quality of the drawing is simply amazing, let alone its bold execution. “His modernist affiliation is crystal clear, and so is the selection of the backdrop, the color, the paintbrush touch and the composition that no doubt make this drawing one of his finest creations.”2

Upon his return to Havana, the Cuban art was not the same he’d left behind when he’d returned to Spain. Some called “modern” at that time were now staunch “academics”. Other painters and sculptors had joined the generation of 1927, and in the wake of the Second National Exposition of Painting and Sculpture “an array of artists who, beyond the circumstantial dimensions, come to us as a clear-cut continuation –from their own individual poetics– of the postulates of the Generation of 1927, is easily made out.”3 Segura isolated himself, he broke away so distantly from both the avant-garde and the most liberal representatives of the Academy. He started working solely on portraits, but never again with that freshness that has marked his early works. His landscapes of the Havana Forest and the street scenes of Havana lost their spontaneity of their early going. He remained active until his death in 1963. Between that date and the year 2000, Segura’s name and work was nearly rubbed out lest the abovementioned exhibit held in 1988. At the turn of the century, Segura’s artworks began popping up from his Cuban family and a number of exhibits are planned to eventually put him on the map for several generations. One of those exhibitions was held at the Spain Cultural Center and was entitled Jose Segura Ezquerro. It opened in March 2000 and culled 32 drawings and oils dated between 1930 and 1962.

Following its grand reopening in 2001, the National Museum of Fine Arts included three works from the artist in its renovated and enhanced Cuban Art Halls. An unjustified absence had been mended, especially after the Avant-garde exhibition has pointed out the undisputed presence of Segura Ezquerro in the modern movement of the Cuban arts.