My movies for a Habano

With his last breath, Citizen Kane drops –till it bursts- a snow globe as he utters the puzzling word Rosebud. Sam Spade, more like Humphrey Bogart than Hammett, goes on a quest for the Maltese Falcon, “what dreams are made of”. The same Bogart in Casablanca, reshot in studios, ordered Sam, the black pianist at the Rick Café, to encore As Time Goes By if he had played it before for Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman). Another Swedish, Greta Garbo, playing the role of a Soviet woman in Ninotchka, fell head over heels with the charms of Paris. Conjured by the Buñuel temper, The Exterminating Angel prevents a group of aristocrats from leaving a mansion. John Wayne, the cowboy par excellence, in the carriage that takes him away as a prisoner, defends passengers from the attack of assailing Indians. The very Janet Leigh, peeved by willows of smokes given off by the cigar of an obese and repulsive cop named Quinlan (Orson Welles) in A Touch of Evil, does not suspect as she takes a shower at the Bates Motel in Psycho, the blend of water and blood from the stabs she will get.

A pickpocket in Pickup on South Street chances upon a microfilm that contains important secret documents in a whore’s purse he robbed in the New York subway. The wind gust that lifts the white skirt worn by a surprised Marilyn Monroe, eager to quench The Seven Year Itch of her married neighbor who lives downstairs. A few years back, it was good enough for her to walk briefly into the office in Love Happy (1949) and notice how her knockout body could make Groucho Marx’s cigar fell of his lips. The smoke from another cigar is exhaled easily as he realized it was nothing but a nightmare; the psychology professor’s (Edward G. Robinson) peaceful life had taken a dramatic turn when he met The Portrait Woman he had watched in a showroom, because dreams will always be dreams…

What do all these scenes from anthological movies have in common? It’s not that most of them were shot in black and white, or that they are all movie classics. Nearly all are masterpieces from the very best movies of all time in over a century of history. However, many people don’t know that their directors –Orson Wells, John Huston, Hungary’s Michael Curtiz, Jewish-Berliner Ernst Lubitsch, Aragon’s Luis Buñuel, Irish John Ford, British Alfred Hitchcock, Samuel Fuller, Austria’s Billy Wilder, Germany’s Fritz Lang, and Groucho, the mustached Marx brother, were not only bound together by their humongous talent, but also by the fact that absolutely each and every one of them played their memorable characters under the influence of a huge amount of habanos.

Who knows how many of those sequences, takes, screenplay solutions or genial gags came out following the puff on a cigar imported from Cuba? They could probably let the megaphone and the clapperboard boxed in a corner, but never a well-stocked box of cigars. Word has it that even Welles once said he liked acting in films because that gave him a chance to smoke cigars for free, or this other statement: “That’s the reason why there are so many heroes and bad guys who smoke cigars. Cigars are my inspiration. The bigger they are, the better.”1

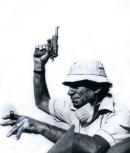

With cigars pressed between their lips all the time, Lubitsch, Welles and Fuller were chain smokers both behind the cameras and off the sets. The latter, a well-known action flick hero, was once shot by Godard back in 1965 with his deep-rooted habano as one of the characters unearthed by Crazy Peter. “A woman is nothing but a script, but a cigar is a whole movie,” Fuller was once quoted as saying.

Film noir is the empire of crime, but also the turf of the habano. Every self-respecting mobster –Scarface, The Blue Dahlia and many other signature films- always keeps a finger close to a gun trigger and a cigar hand-rolled in any Cuban cigar factory. Bogart lit up cigarette after cigarette before and after the one that bound him together –by means of a flame- with Lauren Bacall in that Hawaiian version of To Have and Have Not shot by Howard Hawks in 1945. But Robinson is penciled in as the finest cigar smoker of all time, both on and off the big screen.

The two impertinent smokers worked together under the helm of John Huston (1906-1987). For this outstanding filmmaker, coming to Havana to sail away with Ernest Hemingway in his Pilar boat, hang out in bars and brothels, meant a whole lot more than shooting down here the scenes of his movie We Were Strangers (1949). Gina Cabrera and Alejandro Lugo stunted Jennifer Jones and John Garfield in those shots. The author of For Whom the Bells Toll passed on his wisdom and passion for habanos to the man who later on shot Moby Dick. That was Huston’s companion even when he directed his last two films from a wheelchair –Prizzi’s Honor (1985) and The Dead (1987), as he talked on and on with a cigar between his lips.

“Smoking I wait for the man I love…” says the lyrics of a song in the movie El Último Cuplé (1957) sung by Malaga’s Sarita Montiel, who eventually succumbed to the pleasure of the habano. She always pinned the blame for that on “Jemigüey” (Hemingway), the man she had met at Maria Luisa Gómez Mena’s home and who visited her while in shooting in Havana a trio of coproduced flicks –Piel canela, Frente al pecado de ayer and Yo no creo en los hombres, directed between 1953 and 1954 by Juan J. Ortega. The energetic seducer, relying on letters, powder and some kind of animal charming, dragged her into a short-lived romance. However, she staunchly admitted that the one thing that actually made a difference was that from the very first Partagas he put in her hands, he taught her to light it up, puff on it and not inhale the smoke. “Ernesto used to say I looked very sensual whenever I lit up a cigarette, caressing it rhythmically, almost without touching it, and that’s why I could get along well with cigars,” she wrote in her memoirs. Without even singing the last variety song, hawking it out like a flower seller, nor dancing her last tango, she lost count of how many cigars she burned down to ashes.

As they waited between shots, ready to shout “Action”, these directors wallowed in signature cigars. Those were no doubt the most precious gifts they could get from friends who used to travel to Havana to get three sheets to the wind at the Sloppy Joe’s or dote on the well-built brown dancers from one of Rodney’s show at the Tropicana Cabaret. Also in the 1950s, Cesare Zavattini, the founding father of Italian neorealism –he already had the scripts of Ladrón de bicicletas, Milagro en Milán and Umberto D under his belt- during his first visit to the Cuban capital, got used to ordering a cigar after every sumptuous meal or cup of coffee. Even Marlon Brando, who acted in a cardboard model of Havana in the movie Guys and Dolls (1955), a film by Joseph L. Mankiewicz, made a brief escapade to the real city where he gave free rein to his instincts. He played bongo drums, visited brothels and, of course, he puffed on cigars –he preferred cigarettes long before he acted for John Huston in the movie Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967).

In this sort of Cuban controversy between cinema and tobacco –to paraphrase Don Fernando Ortiz- we opt to make a pause in those cigar smokers without interrupting those the history of the film industry owes to so much. Like King Richard III and hiss horse, they couldn’t do without that transfusion of black-grained film, neither with the exquisite aroma and taste of a genuine Cuban habano rolled in Cuba.